• Ecua-Beat. The difficult to describe (without an audio example anyway), yet musically simple, ever-present thumping heard day and night. You know it when you hear it, and will come to recognize it after only a short while in Ecuador. The beat is the same, but the lyrics change, an easy fix to the problem of composing new songs. From a distance, it is impossible to know which tune is playing since the music sounds the same. The best, or shall I say most entertaining, goes something like this: “Say, Say, Say, Say, Say, Say….” over and over and over again. The lyrics in this case are as inspired as the beat. After enough time in Ecuador, with gradual numbing of the senses, it becomes something like white noise and you notice it less and less.

• Ecua-Walk. The telltale stride of the Ecuadorian. The feet aren’t quite lifted off the ground, but scuffed along, effectively slowing the pace. I’ve practiced this many times, with failed results, making it seem as though you must be Ecuadorian to really get it down. To further slow down the rest of pedestrian traffic, they’ll just stop randomly in front of you, and look around, or chat with another Ecuadorian. Once, during the high point of our Ecua-walking career, we shuffled along, and inadvertently stopped right in the middle of the sidewalk, continuing to talk, apparently having lost all necessary momentum to sustain the act of walking. The reaction of the Ecuadorians was to actually laugh and stare at us; obviously, gringos Ecua-Walking does not have the same effect.

• Ecua-Volley. “What is this, Jungle Ball?” and “No Monkey Hits!”, the words of my High School Volleyball coach, scolding us for poor form during practice. I never quite understood the whole Jungle Ball comparison; I only knew it implied rule-less play with little or no technique. Until I came to the Jungle, where the men fervently play on open-air courts. It is almost religion in Ecuador. They are fiercely competitive, playing in teams of three. Anything goes, it seems: the ‘bump’ is two hands meeting but never fully clasped, often open-palmed to send the ball upward; the classic volleyball ‘set’ is more of a catch and throw, and is often done from the back row; the ‘spike’ is usually more of a cradle with the full palm, lobbing it, rather than driving it downward, over the net. Great entertainment.

• Ecua-Knot. Perfected by the market ladies, who seem to have it down to a science, but tied by all, the Ecua-Knot is an extremely tight, seemingly inside out and twisted, impossible to undo knot used to close plastic bags. I have spent much time watching them execute the knot, but cannot seem to perfect it myself. You can be sure that nothing is going in or out of your bag to spoil your purchases. The slippery plastic does nothing to aid in the knot’s removal; wanting to reuse bags here is a challenge, as you often end tearing the bag open in frustration.

• Ecua-Cambio. Or more aptly, lack thereof. A shortage of change is something you learn to expect, and fully anticipate, in this country. Even the bank sometimes can’t break a $50 for you, or can only give you 20’s, which doesn’t help your predicament when you want to buy something for .50. But, I have learned, thanks to adequate language skills, that you can call their bluff 99% of the time. They often have the cambio; they just don’t want to give it up, especially to a tourist. The issue of change becomes part of conversation, and even warrants bragging rights when you really score: Not having to wait very long at the bank, and getting twenty 5’s for your $100 takes the cake in the cambio department.

• Ecua-Signage. “Internet? Why would you think we have Internet?”, said with an expression clearly indicating that this Ecuadorian thinks you are just plain crazy. “Why? Because it is PAINTED on the outside of your building, that’s why.” And painted in big letters, nonetheless. Or, getting the same reaction by asking about the Meriendas (set dinner, usually cheap) that are advertised, again the huge letters painted on the wall right behind where the orders are taken in the restaurant, suggesting permanent availability. One does have to wonder though if it’s just that they don’t want to sell you the Merienda when they know they can charge you twice as much for the same meal a la carte.

• Ecua-Presence. Apart from the Quechua, most Ecuadorians seem to want the world to be aware of their presence, at all times. They do this by making as much noise as possible, in any given context. They may even be in competition with each other for who can make the most noise: outdoing the neighboring businesses’ blasting of the Ecua-Beat; who can honk the loudest and most often, from buses to taxis to motorcycles, they all honk incessantly; loudspeakers the roof of a car is a common sight and a well-used noise-making device; the ‘whap’ produced by women smacking their wet laundry on the rocks in the river, which supposedly, albeit questionably, better cleans their clothes; smacking the buildings/structures as they walk by with a bottle, stick, whatever they have; a young boy making the second most annoying noise known to man (after fingernails on a chalkboard): rubbing a balloon with his sticky palm as he walks the entire length of the main drag. With a seemingly bottomless quiver of noise-making tactics to draw from, you can never doubt the presence of an Ecuadorian.

February 22, 2006

February 20, 2006

Cup of Tea, Sit in a Comfy Chair

Pouring rain here in Tena. The socked in, foggy downpour kind that looks like it might be here to stay for a few hours.

It’s not often that I have wanted to make a cup of tea in the jungle, especially at midday. By now the heat is usually oppressive and hard to bear, the last thing you want is a hot beverage. Today is different, and I’m contemplating what to do with myself. To escape the heat, I go to the river, but right now that doesn’t seem quite as appealing to me.

Part of the challenge for me while being away from home is learning to relax, and be at peace with having nothing to do. Nowhere to be, no projects to finish, no work to do or plan, no cleaning to do…it’s freedom in every sense of the word, once you manage break free from yourself, and more importantly, your expectations.

I am, admittedly, not a very good tourist. I prefer to live in a place, find routines, and be a part of what’s going on in one place. Hopping from city to city, country to country, culture to culture is not my cup of tea. I usually find a place I like and settle in, and prefer to make my observations of that place over a longer period of time. It seems ironic, then, that I would have a hard time relaxing when being in one place is my preferred MO; one would think I would really enjoy the everchanging scenery that comes with being more a more nomadic traveler.

For me, traveling isn’t only about seeing other places, but is more about discovering parts of myself while in another place. Parts of me I didn’t know were there, that I may or may not like or accept. The learning comes in truly seeing these sides for what they are, when they show themselves, and deciding whether or not to let them emerge more regularly or often. It involves cultivating a growth that would probably not happen at home, immersed in comforts and excess of modern society, your native tongue, and familiar systems.

So for now, today, I will do my best to relax, hang out, and think. I will look inward a bit and explore myself as I might the Ecuadorian countryside, a journey that is far more arduous than even the gnarliest Andean terrain. It is an adventure that requires more courage and patience, no expectations, just an open mind. And sitting still, in a comfy chair (ok, maybe not, it's a plastic lawn chair), sipping tea in the middle of the day, as I would in NW wintery weather, is a good a place as any to begin.

It’s not often that I have wanted to make a cup of tea in the jungle, especially at midday. By now the heat is usually oppressive and hard to bear, the last thing you want is a hot beverage. Today is different, and I’m contemplating what to do with myself. To escape the heat, I go to the river, but right now that doesn’t seem quite as appealing to me.

Part of the challenge for me while being away from home is learning to relax, and be at peace with having nothing to do. Nowhere to be, no projects to finish, no work to do or plan, no cleaning to do…it’s freedom in every sense of the word, once you manage break free from yourself, and more importantly, your expectations.

I am, admittedly, not a very good tourist. I prefer to live in a place, find routines, and be a part of what’s going on in one place. Hopping from city to city, country to country, culture to culture is not my cup of tea. I usually find a place I like and settle in, and prefer to make my observations of that place over a longer period of time. It seems ironic, then, that I would have a hard time relaxing when being in one place is my preferred MO; one would think I would really enjoy the everchanging scenery that comes with being more a more nomadic traveler.

For me, traveling isn’t only about seeing other places, but is more about discovering parts of myself while in another place. Parts of me I didn’t know were there, that I may or may not like or accept. The learning comes in truly seeing these sides for what they are, when they show themselves, and deciding whether or not to let them emerge more regularly or often. It involves cultivating a growth that would probably not happen at home, immersed in comforts and excess of modern society, your native tongue, and familiar systems.

So for now, today, I will do my best to relax, hang out, and think. I will look inward a bit and explore myself as I might the Ecuadorian countryside, a journey that is far more arduous than even the gnarliest Andean terrain. It is an adventure that requires more courage and patience, no expectations, just an open mind. And sitting still, in a comfy chair (ok, maybe not, it's a plastic lawn chair), sipping tea in the middle of the day, as I would in NW wintery weather, is a good a place as any to begin.

February 16, 2006

Plentiful, Cheap, and Good

Thoughts of home are peppered with a longing for familiar things, a system I understand, and a feeling of belonging. Being away from home truly makes you cherish what you have, where you live, and the people that make it feel like 'home'; it is always upon returning that I can fully grasp the experience of traveling, and can see how it has affected me. It is this process that makes traveling feel so good: learning about yourself simply by gaining an understanding of a culture and land that is unknown, in an often uncomfortable and stressful context, where some days all you want is some peace and quiet, a respite from the obnoxiously loud bus and truck traffic, honking taxis, and never-ending 'ecua-beat' heard on every block, everyday and night. When you can just walk into a store and buy something without being ignored or pushed out of the way by an Ecuadorian who is uncharacteristically in a hurry. These are the moments when traveling is anything but glamorous.

But I digress. What I wanted to ponder here wasn't the not-so-nice aspects of a developing Latin American country, but the so wonderfully positive things that I can't let myself forget.

The Latin American system of small shops is both mind-boggling and refreshing; there must be at least 2 or 3 on average per block here in Tena. I can't get my mind around either the economics or the business strategies of these shops, mainly because they are so numerous, all sell the same things, and what's more, all seem to charge the same price. I personally love it because if I run out of something while cooking, it is guaranteed that I'll find it within minutes, and I don't have to be concerned with bargain shopping.

And speaking of bargains, nearly everything in Ecuador is cheap. It's all relative, of course, but everything is, generally speaking, about 5 times cheaper than in the states. I can eat on about 2.50 per day here, doing my own cooking. Because Ecuadorian cuisine isn't exactly inspiring, I find that it's healthier, safer, and cheaper to cook at home. The produce here, depending on where you are, is amazing. Here in the jungle, some things are hard to find, like spinach, lettuce, etc., crops that like it on the cooler side, but even so, you can't complain when you can buy 3 mangoes or 2-3 avocadoes (big ones!) for a dollar. Today I visited the market and bought the following for about $7.00: 5 tomatoes, 3 onions, 2 heads of garlic, 2 chili peppers, 3 mangoes, 2 avocadoes, 6 granadillas (also called 'snot fruit' or 'frog egg fruit', member of the passionflower family, tastes amazing, much better than the name implies), cilantro, 5 limes, 1 cucumber, 1 bell pepper,1 pound of rice, 1 pound of pasta, laundry/dish soap, and chicken stock. Even when it's not full on market day, the produce is still awesome. The market ladies compete for your business, but I often try to just spread the wealth unless one stand has an irresistible selection. I love the market ladies, and have actually learned a lot about produce and Ecuador by talking with them. They almost always give me free tangerine or something when I buy a lot.

And speaking of bargains, nearly everything in Ecuador is cheap. It's all relative, of course, but everything is, generally speaking, about 5 times cheaper than in the states. I can eat on about 2.50 per day here, doing my own cooking. Because Ecuadorian cuisine isn't exactly inspiring, I find that it's healthier, safer, and cheaper to cook at home. The produce here, depending on where you are, is amazing. Here in the jungle, some things are hard to find, like spinach, lettuce, etc., crops that like it on the cooler side, but even so, you can't complain when you can buy 3 mangoes or 2-3 avocadoes (big ones!) for a dollar. Today I visited the market and bought the following for about $7.00: 5 tomatoes, 3 onions, 2 heads of garlic, 2 chili peppers, 3 mangoes, 2 avocadoes, 6 granadillas (also called 'snot fruit' or 'frog egg fruit', member of the passionflower family, tastes amazing, much better than the name implies), cilantro, 5 limes, 1 cucumber, 1 bell pepper,1 pound of rice, 1 pound of pasta, laundry/dish soap, and chicken stock. Even when it's not full on market day, the produce is still awesome. The market ladies compete for your business, but I often try to just spread the wealth unless one stand has an irresistible selection. I love the market ladies, and have actually learned a lot about produce and Ecuador by talking with them. They almost always give me free tangerine or something when I buy a lot.

This is going to sound really silly, but I also love the dogs here. They are so truly free. Most have homes, but they really just do what they wish, roaming the streets, often congregating at the meat shop to drool and hopefully catch a scrap or bone. We’ve managed to name many of them: Ramon’s friend (see post titled ‘Ramon’ in my archives) lives kitty-corner from us; Hang-Ten on the roof across the street; Fluffy 1 and 2 live just down the block; Socks lives at the end of the block; Penny lives near the panaderia (bakery); Orejas (ears [2 inches of dog, 6 inches of ears, feared by dogs of all sizes]) lives near the river; and last but not least, 2-face lives directly across the street on the ground floor. He is my favorite, some sort of pit-bull/terrier type mix, huge and white with markings on his face, one side being mostly black with some brown, and the other white, hence our name for him. Turns out his real name is “Pirata”, or Pirate, also fairly descriptive.

It isn’t his looks that win me over, but his personality. This dog has some character. He sits around, looking so serious and pensive, usually inside of his 9’ tall concrete/iron fence with spikes on top. One day, I saw him approach the fence from the outside, and launch himself onto it, clinging onto it halfway up, then climb the rest of the way, up and over the top. He looked like a cat! But he must weigh in at least 70 lbs.! It was impressive. We told our friend Matt, who lives below us about seeing this little feat, and he says “Oh yeah, he does it all the time. You gotta watch out for that dog, he’s strange.” He then proceeded to tell us about the time he saw a bus stop on the corner, the door open, and 2-face get off the bus. ALONE. No owner, just the dog. Somehow that freaked Matt out, but I tell you, I never laughed so hard. Many questions came to mind, the obvious ones, like how in the heck did he end up on the bus in the first place? How did he explain where he was going or know which bus to choose? Furthermore, how did he tell the driver it was his stop coming up? I mean, did he say “Gracias” like everyone else? And how on earth did he pay the fare?! The mental image of this whole scenario is almost too much.

His owner told me that jumping the fence is how he comes and goes; I wonder if she knows about the bus rides?

Anyway, the dogs are an aside, but honestly they have made my stay in Ecuador quite entertaining. They aren’t like American dogs—they’re street smart, independent, and really don’t like your attention. They are in some way more wild, not so domesticated. It’s quite refreshing, really.

I'm off on one tangent after another, my head spinning as I try to process what the past 2 months has meant to me, something that may be impossible to sort out while still living in this culture. My title was meant to refer to the abundance of produce, food, water, and life in Ecuador. The tremendous diversity that seems never-ending, but in reality is threatened all because it is cheap, plentiful, and good. My intent was to dive into the positives so that my mind would be open to the possibilities that exist here for me to thrive. In doing so, however, I can't be so discriminating. For every yummy granadilla that comes off the vine, every fresh banana I eat, there is a price, though minute in monetary terms for the consumer, it tremendously impacts ecuadorian livelihood. Rainforest is cut down at alarming rates; coming from a logging town in Idaho, I am no stranger to large-scale harvesting. The chainsaws they sell here are HUGE, indicative of the size of the native trees being cut down, all to grow bananas and coffee for export, even when it is well-documented that coffee grows much better in it's shady native understory. The precious rivers, a source of life and sustenance for so many Ecuadorians, are being damned and mined, we see it happening in front of our apartment. Digging for sand and gravel to build roads, in the name of development and modernization. The oil pipeline between here and Quito bursts and leaks, polluting the rivers and streams, all so we, in the US can drive, drive, drive...to where and why, I'm not even really sure.

It's all easy to see from an outsider's perspective, the red flags that mark their "progress", because my own country, as well as other developed nations, has gone through the same process. I can hardly compare Latin America with the states, but economically and culturally speaking, many countries here are trying to attain a way of life that seems superior to their own. They want what they see on american TV, at the cost of their environment, health, integrity, and rich cultural history. It is a complex web of peer pressure, driven by the ever intensifying global economy, and steadily increasing greed and materialism that is spreading like no virus ever could. And unlike other viruses, isn't being fought, but perpetuated, marketed to the point that I believe no culture is unaffected.

Who am I to say what is right and wrong about how different societies choose to operate? It would be terribly judgmental of me to think that there is a right way or a wrong way, or to say that Latin America shouldn't try to achieve economic success, when they are every bit as entitled as any other country in the world. I suppose the difficulty comes in having to sit back and watch it happen, when you feel you can see that the path they are headed down will probably only lead to more disparity, inequality and lower quality of life, once they export all of their 'assets', meaning their natural resources, away.

What started as a light-hearted commentary on the great things about Ecuador has turned into much more than that. Funny how simply thinking of abundance and life led me to consider the cost of enjoying it. But, even so, I still feel better about buying my food here straight from the Quechua growers, the market ladies, knowing that there is no middle man involved, that I am supporting their community and contributing in some way to a lifestyle I will always respect more than anything else in this world. A lifestyle where there is fresh food on the table, where the farmer grows more than one crop, honoring and modeling nature's ways with diverse farms that aren't too sprawling and never corporate. A life that can be simple, where kids still play outside, where the even the dogs enjoy a sense of freedom, and one knows where their food comes from. A life where the things that really matter--culture, family, living in the moment--are, and hopefully will remain, plentiful, cheap, and good.

Photos, top to bottom: Granadillas on the vine; Market Lady; Abundance in Baeza; 2-Face; River Gravel Mining; Young girl at Market; Ecuadorian Daycare

February 13, 2006

Carla the Stripper

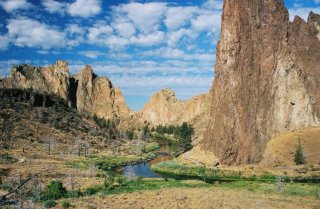

I’ve been called out on not having anything about climbing on my blog yet, so I thought I would share a story of one of my first-ever climbing experiences at Smith Rock State Park in Central Oregon.

It was a spectacular March day, more than 70 degrees with sunny skies. I think it was Walter and I’s third weekend in a row. We left late on Saturday night, and slept out under the stars (it was frickin freezing, frost on the bags). Walter wanted to drive to the end of the road to camp, so we ended up sleeping pretty much in the middle of the road. We woke up super early, and drove to the park, the first ones to arrive at 7 am.

Per usual, we warmed up on 5 gallon buckets, a huecoed out, beautiful 5.8 that Walter normally climbed barefoot. Spreading out the old windsurfing sail Walter employed as a rope bag/tarp/emergency shelter in a pinch, we climbed Buckets and the 5.9 next to it. In typical Walter fashion, he gathered up the flaked out rope in the sail (which is, I might add, full on 80’s colors, white with pink and turquoise…and who knows what other colors. But I have no room to talk with my anodized turquoise/magenta quickdraws, aptly nicknamed the Duran Duran draws), hobo style, over his shoulder and proceeded to practically run to the next routes while I’d barely begun to unlace my shoes.

Per usual, we warmed up on 5 gallon buckets, a huecoed out, beautiful 5.8 that Walter normally climbed barefoot. Spreading out the old windsurfing sail Walter employed as a rope bag/tarp/emergency shelter in a pinch, we climbed Buckets and the 5.9 next to it. In typical Walter fashion, he gathered up the flaked out rope in the sail (which is, I might add, full on 80’s colors, white with pink and turquoise…and who knows what other colors. But I have no room to talk with my anodized turquoise/magenta quickdraws, aptly nicknamed the Duran Duran draws), hobo style, over his shoulder and proceeded to practically run to the next routes while I’d barely begun to unlace my shoes.

Eventually we made it to the Phoenix Wall, where I had never climbed. The texture of the rock is different here than in much of the park, my fingertips were trashed after only 3 routes, the hardest of which was a 5.11 something, the crux a nasty bulge to pull over near the top. Having nearly killed (an exaggeration, but scary nonetheless) Walter the weekend before in Cocaine Gully because I was not anchored down while belaying him, and was dumb enough to sit about 20 feet from the wall while lowering him on TR, I decided to anchor into a tree for this route, as Walter had never led it before and well, it just looked heinous. He pulled it off without incident though, which meant I had to lug my butt up it to clean it.

At this point it was about 1:30, and the park was a zoo, filled with all the weekend warriors from Bend and Portland. We had already climbed about 7 routes, more than most people do in a full day of climbing, but Walter thought we should hike over to the Marsupials on the eastern edge of the park, a couple of miles away from where we were. I was tired, but couldn’t resist the challenge.

Once in the Marsups, we climbed a newer route, grade 5.10 something called “The Edge of the World.” Because it had this heinously exposed traverse that was awkward, and just plain nauseating, we re-named it “Edge of the Hurl”, and demoted it from a 3 star route to a 0 star route in the guidebook. From here, we hiked up the hill to climb the 3 beautiful, but juicy, routes on the backside of Brogan Spire. By the end of the third, an overhanging 5.11b, I was totally wasted. But, since it was still daylight, we weren’t finished quite yet. Hiking down the hill, and doing a little class 4 scrambling, we ended up on the north side of the Spire, where Walter proceeded to do a one-move wonder short pumpy, boulder problem-esque little route that I don’t remember the name of, next to Tuff Shit. Thinking we were surely done, as we had about a 45 minute hike out, and it was growing dusky, I started to take my shoes off, completely exhausted but satisfied with a great day of climbing. Walter had other ideas. Just down the trail from us, there was a multi-pitch 5.7 called Carla the Stripper. I started to object, but Walter argued before I could utter a peep, “Val it’s only 5.7!”. I later learned to just say no to Walter, as advised by all of his friends, but at the time I was still naïve, and easily persuaded due to my enthusiasm for climbing.

Walter set off, and I wearily belayed him, thinking about how insane this was. When he got to the top, he pulled the rope, I tied in and started climbing, knowing full well we would be rappelling in the dark. This little 5.7 felt like a 5.10 to me, or worse, and it took a lot of effort to make it up, even on top rope. Once I got to the top, as the last vestiges of daylight dwindled, and Walter said “Ok Val, now, here’s what we’re going to do so we don’t have to set up 2 rappels. You are going to traverse over to the Tuff shit anchors, I’ll keep you on belay, and when you get there, you can just clip in, pull the rope and belay me over.” “Why me first?” I asked. “Because, you are already tied in”, he answered. So, I was going to traverse this exposed ridge, having no idea where the hell I was going, completely dehydrated and exhausted, practically in the dark? At that moment, I was pretty sure I was going to die. But I felt that I had no other choice, so I timidly starting walking. Luckily, I found a bolt to clip into about halfway over, so that if I fell while downclimbing to get to the Tuff Shit anchors, the swing wouldn’t be quite as bad. By the time I found the chains, it was pretty much dark. Walter headed toward me, and I wondered if he had his headlamp with him. Once he arrived, we set rappel and I went first. It was interesting, in the dark. I never would have admitted it at the time, but it was actually quite fun. And no, Walter did not have his headlamp for the rappel, but did have it in is pack. I did not have mine, but ever since Carla the Stripper and the midnight rappel, I have always carried one with me.

Hiking back in the dark would have been straightforward, but Walter wanted to take a short cut, so we ended up cross-countrying it to get to the Burma Road, walking straight downhill and crossing a huge dry irrigation ditch. The rest of the hike is easy, and you think it’s gravy…until you get to the part where you have to climb out of the river canyon to reach the parking lot. The trail switchbacks its way up the hillside, not normally difficult really, but after an epic day like ours, it was brutalizing.

My car was the last one left in the parking lot. Walter climbed 13 routes that day, and I climbed 12. Because Walter is an engineer, and German, he actually calculated our average grade for the day. I can’t remember it now, but it was high, 5.9 or 5.10a maybe. I was more amused by the fact that he actually spent time finding the average. I’ve never been so tired, and the next day, I couldn’t actually open my hands at all!

That would be my last trip with Walter until late fall. He was off to Everest Base Camp in April for 6 weeks, and I would have other things going on. He did point out to me that in three days that March, we climbed about 33 routes, which provided me with an excellent base for the season. I look back on that now, and I miss those days. I really did live for climbing, and had an undying enthusiasm that would be quelled only by injury; I developed severe tendonitis in both elbows the following November, and haven’t been able to climb that hard since. Most people say I did too much, too soon, but I have a tendency to disagree. I was passionate, and I loved every minute of it. Had I just dabbled, kept my climbing on a schedule, it might not have been so fulfilling and rewarding. Throwing myself into the sport saved me from other things going on in my life, and being a reasonably capable beginner motivated me to continue pushing hard. It also gave me a confidence and belief in myself that I needed at the time to figure myself out, and get to the point where I could accept myself for who I was.

I still climb, but last year’s season paled in comparison to my first. I was forced to take it slow, be patient, allow myself to rest in order to ward off bouts of tendon flare-ups. I started climbing with the BOPS (Bitches on Pitches) all women climbing group based out of Redmond. I have better learned to relax, to laugh, and that it is ok to be a part-time climber if that is what I need to be. Carol Simpson, co-owner of Redpoint Climbers supply and First Ascent Climbing Guide Services, is a real inspiration to all of us girls out there. She has been climbing for 20 plus (??) years, is as enthusiastic and motivated about climbing as I was my first season, and is amazing to watch as she floats up the rock. Most of all, she has fun out there, enjoys a beer afterward, and is always psyched to be out there. In a male dominated sport, it is refreshing to see a gaggle of gals queuing up on some heinous crack in the Lower Gorge, cracking up over some dirty joke that Carol or Steph has just told. It is a reminder that, ultimately, this is why we climb. Because we love it, no matter how difficult or easy it seems at the time, or how hard we are pushing ourselves, we love feeling the rock at our fingertips, seeing the ground below, and the feeling of accomplishment that comes with reaching the anchors. Even in the dark.

Photos, top to bottom: Smith Rock State Park, Walter and me at the base of 5 gallon buckets (Nov. '04), Walter carrying the sail hobo style, Me, on Blue Light Special, The Shipwrecks (Nov. 04), and Walter, Trout Creek Cracks (June '04).

February 10, 2006

A Perfectly Good Airplane: Part III

It was sooner rather than later that I found myself back on a plane to Mexico City, then on to Puerto with a one-way ticket, having spent 2 weeks in the states. Most thought I had lost my marbles somewhere on the beach in Mexico. Well, to their credit, I had. But I had found myself along the way, and I felt free, completely alive, and exceedingly happy to be who I was. So much so that I sold a few possesions, moved my things into storage, busted out a painting job, and off I went to live in Mexico for an undetermined amount of time. My life in the states had to wait; returning to Mexico to work was something I could not pass up.

I arrived in Puerto on an AireCaribe jet. As we landed, I could see the skydivers loading up the Otter in the far corner of the tarmac. I waved frantically, and considered the possibility of running over and going up with the load just to be in the plane again (turns out my friend Tris tried to come over to give me her parachute so I could really have a proper homecoming, but they wouldn't let her cross the tarmac to do so). But, airline procedures wouldn't allow this, so I had to refrain and go through customs, where they promptly confiscated a banana that I had puchased in Mexico City but had not yet eaten. They almost fined me for it; luckily my spanish skills could argue otherwise, and I was spared.

I did feel like I was coming home. All of the divers from Cuautla were in Puerto for Semana Santa, as were plenty of tourists. I went right to work the next day, organizing flights, logistics, rousting tandem instructors to get out of bed in the morning. My job was a little like herding cats (said the gringo pilot Kirk); here was a little gringa telling these guys what to do. I have to admit, I enjoyed it! Deep down, they did as well, although I think they found me annoying at times, having waaay too much energy for the beach in Mexico, where "ahorita" technically means "right now", but can mean anywhere from 5 minutes to 2 hours from now. I also heard it used to refer to 10 minutes ago. The concept of time just really doesn't exist, so my boundless energy and american effiiciency and work ethic drove them nuts at first; in the end, however, they were grateful to have so many plane loads going up. My first day, we had 12 flights, a new record for Skydive Cuautla in Puerto. Money talks. They really couldn't resist calling me "Sargento" (sargeant) though.

After Semana Santa, the tourists and the skydivers left. Flights were to a minimum, and tandems had to be worked for. Head salesperson Fernando recruited most of them from the beach, mainly women. I did my job, but it was really casual now and I had plenty of time to jump as well. I rented a cabana near the beach from a darling couple named Tacho and Pati. It was cheap, private, and safe.

The skydiver lifestyle is very carefree. The guys live in the moment; they eat, breathe, and sleep skydiving. They live at the drop zone in a trailer, and most have no debts, just spend their money on cameras and parachute rigs. And chelas. Lots of chelas. When a person does something stupid, they buy chelas for all. When you do something for the first time, it's "chelas" again. When something is done well--ah, "chelas". You really can't win! And you learn to stop sharing new experiences, knowing you'll certainly owe chelas. Most of the time its a joke, but they don't complain when you oblige.

Favorite skydiver expressions: "My drinking partner has a skydiving problem"; "When skydiving interferes with your work, it's time to quit your job"; and Tris and I's qualifier for "how you know you've been hanging around Skydive Cuautla for too long": When you are standing on a tall bridge and you say to yourself 'Nope, too low'. Another classic was the guys telling a 6 year girl (jokingly of course) that SHE had to buy chelas after her first tandem jump! (The funny part was, her parents actually bought chelas).

The party oriented lifestyle was new to me, having always been outdoorsy and relatively fit. I enjoyed it for awhile, and managed to maintain a balance by running on the beach nearly every day to La Punta and back, doing yoga, and trying not to drink too many yummy Pina Coladas. The guys went to Cuautla on the weekends; I chose to hang in Puerto with my friend Whitney. Admittedly, I enjoyed the time off, not that my job was really "work" in any sense of the word, but skydiving did seem to monopolize my time a bit. 12 hours of the day were spent in skydiving mode, so the weekends let me go surfing (ie, get my butt worked over on a surfboard) and do other things. I think that the time spent on the beach waiting for the skydivers to return was the first time I really let myself relax. I was still fairly spastic, but I did mange to loaf around more than I ever had before.

By mid-April, it was hot--Africa hot--and we slowed down. The following week, the week of my 30th birthday, the guys didn't come to Puerto, and I was crushed because we had a huge group jump planned with me riding horsey style on someone's back. They had to switch pilots from Skydive Chicago, so had no choice but to wait in Cuautla. There were always mixed feelings about coming to Puerto when the tandem potential was low. They spent a lot of money there, so sometimes it wasn't worth it. But they loved the beach, the girls, and of course, jumping over the ocean. Sea level affords going to higher altitude than they can in Cuautla, which sits at nearly 6000'. The difference is more than 3000' higher, and about 20 seconds more of freefall.

By mid-April, it was hot--Africa hot--and we slowed down. The following week, the week of my 30th birthday, the guys didn't come to Puerto, and I was crushed because we had a huge group jump planned with me riding horsey style on someone's back. They had to switch pilots from Skydive Chicago, so had no choice but to wait in Cuautla. There were always mixed feelings about coming to Puerto when the tandem potential was low. They spent a lot of money there, so sometimes it wasn't worth it. But they loved the beach, the girls, and of course, jumping over the ocean. Sea level affords going to higher altitude than they can in Cuautla, which sits at nearly 6000'. The difference is more than 3000' higher, and about 20 seconds more of freefall.

I made my 50th jump near the end of April, and of course, had to buy chelas. I learned to pack a parachute, my friend Pana's (because it was a small canopy, easier to deal with), and I always stood on the ground looking up, waiting to see the green, black, and white canopy to open properly. Pana was always saying "oh,it'll open, relax. You have to tie it in a knot for it not to open"; it was more the issue of HOW it opened, not that it wouldn't. My 20th jump was from a helicopter in Cuautla (yep--chelas again), my most personally satisfying, and terrifying, jump. I love helicopters, and have spent lots of time riding in them fighting fire in Idaho. Jumping from one was amazing. You had to stand out on the struts, and just sort of fall off. So quiet and peaceful, and the closest to feeling like you are falling (not much forward speed from a moving helicopter so less initial resistance). The freefall was short, and you could see other people in freefall relatively closeby (again, less forward speed, jumpers end up closer together). Tonio gave up his spot so I could go, saying to Tris and I that it was an amazing opportunity, as he knew people who had 1000 jumps, and hadn't gotten to do it from a helicopter.

We jumped with Tonio a lot, doing Relative Work (flying with other people, approaching them, hanging onto one another--the basis of multi-diver formations). On our own, Tris and I jumped together and practiced approaching each other in the air. It was challenging, as we were both at the same level at the time. Flying in the air with another person in indescribable. Seeing their face up close and waving goodbye, turning and tracking away from them so you can pull your parachute at the agreed upon altitude (one person a bit higher than the other), then landing near each other on the beach.

As the time neared for the plane to return to Skydive Chicago to begin their season, I began to consider my options. The season in Mexico was winding down; with the loss of the Otter, there would be no more jumping at the beach, and therefore, not a lot of work for me. Tonio said I could help out in Cuautla, but that meant only weekends, and an occasional stint in Cuernavaca recruiting tourists, and in Mexico City helping Hector in the office.

It was a tough decision, as May would be the start of potential work for me at home. I also had an offer from Skydive Chicago to work manifest there for the season. I was really torn, and oscillated between the three options, not wanting to miss out on climbing season back at home, my friends in Mexico, or the opportunity to make tons of jumps in Chicago. I really wanted to do all three.

In the end, after 12, nearly 13, weeks in Mexico, I found myself on another plane. This time, I would be flying home in the Twin Otter, back to Skydive Chicago, where I would potentially work manifest. My friend Whitney and I loaded up in the plane, a road trip of sorts, with Woody the pilot and set off for a two day flight (this is all an entry of it's own) to the US, at 18000' and below.

I spent a few days in Chicago, checking the place out. Completely broke, I had to return to the Gorge and figure out what to do. I had mixed feelings about living in the midwest. The job was only part time, and I wouldn't be able to save a dime for the next year's traveling adventures. I would get to jump to my heart's content, which tempted me. But the thought didn't thrill me; I think that part of the romance lie in where I was jumping: the beach, in Mexico. The spontenaeity and carefree lifestyle, in lawless Mexico where you CAN ride in the back of a truck and walk down the street with a beer in your hand. Somehow, though I knew it could potentially be amazing, jumping over cornfields and living so far away from the west coast just didn't appeal to me. Maybe I wasn't ready to commit to skydiving to that extent ?

Once in the gorge, I pondered my options. I love the mountains, summer, and being active. This is a part of me that I just am not willing to compromise for anything. The reality was, I was ready for a break I think, from the Mexican diet of Pina Coladas and guacamole (holy schmoley!), and from drinking so many chelas. It was fun for awhile, but, like anything else, it lost it's novelty when it became too ordinary.

I can't say there is an end to this story, not yet anyway. I haven't skydived since Mexico. It just hasn't felt right, without the beach, the camaraderie, and the concept of "ahorita".

To say that I'm a skydiver feels wrong to me. I don't do it as a lifestyle, and I don't live it like the real skydivers I know. I can say, however, that there is a skydiver somewhere inside of me, waiting for the right time to emerge, perch herself in the door of a Twin Otter, and jump once again from a perfectly good airplane.

Photos, top to bottom: AFF course graduees; Zicatela Beach from altitude (Photo Daniel "Pana" Angulo); Pana landing on the beach; My 30th birthday in Mexico; 3-way (Photo Pana); Tracking Dive, out the door (Photo Pana); Val and Rifle (Photo Pana)

February 9, 2006

A Perfectly Good Airplane: Part II

He was right. I was screwed. I couldn't help myself, and despite the cost and an excruciatingly painful ear infection, I did another tandem the next day. Tonio gave me a fat discount, which made it a bit easier to justify. The second tandem was also with Fernando, and this time, he let me pull the parachute! It was even more exhilerating than the first jump.

Thinking it couldn't getting any worse was a premature assumption. Right before the last load, the sunset jump, Tonio offered me a price I couldn't refuse, and I did a third tandem with Fernando! The bad news was, they just kept getting better, impossible to resist. This time we exited the plane doing a forward flip, and he let me steer the parachute. Tonio jumped with us and I experienced flying in the air with another person for the first time. Amazing!

Well, Tonio knew he had me at that point. I mean, 3 tandems?? He actually cut me off, and said, no more. If you want to keep jumping, you have to learn to do it by yourself. Now that seemed crazy to me, but even so I was secretly glad the divers were returning to Cuautla (the principal drop zone south of Mexico City) for the weekend, as I feared I would not be able to stop myself and end up taking the course.

The following Wednesday, the guys arrived, falling from the sky once again. I was shocked to see Rifle (Gustavo) wearing a cast (a soccer injury), but still able to skydive with a broken foot. I happened to be on the beach and one of them landed right in front of me. It was Pana (Daniel), and the first words out of his mouth were "When are you starting the course?".

The following Wednesday, the guys arrived, falling from the sky once again. I was shocked to see Rifle (Gustavo) wearing a cast (a soccer injury), but still able to skydive with a broken foot. I happened to be on the beach and one of them landed right in front of me. It was Pana (Daniel), and the first words out of his mouth were "When are you starting the course?". To my surprise, as if possessed by another being, I answered "Right now."

It really was the beginning of the end for me. I finished the Accelerated Freefall (AFF) course in 2 days, starting in Puerto and finishing in Cuautla. It consists of 7 jumps with an instructor after some classroom instruction and lots of dirt dives. You have to pass each level before moving onto the next. To assist with landing, you wear a radio and your instructor guides you in from the ground. As you progress, you become more responsible for yourself, and by the last jump, you leave the door diving out with no instructor hanging onto you, and you land by yourself.

Jumping solo can't even compare to doing a tandem. It is incredible. The first time you open the chute by yourself, and then realize you are all alone up there is both exciting and terrifying. My first jump went well, but I hadn't turned my radio on in the plane, and as I lost altitude, I could see Pana on the ground, wondering why he wasn't telling me what to do. I started to panic, thinking I was going to have to land this thing by myself, but then realized the radio was off, turned it on and could hear him a bit frantic trying to talk to me. I landed on my feet, much to my great surprise, and stood there, shocked by what I had achieved. It was sunset, and there really aren't words to describe how I felt, there on the beach, in Mexico, parachute in hand.

The zone in Cuautla was busy, so I ended up finishing the course with Tonio. As is the Mexican skydiving tradition, new graduates of the AFF program are honored by a graduation ceremony. I was told I had to buy 2 cases of WARM chelas (beers) before we could start, and I instantly smelled a rat. All of the skydivers, no fewer than 40, gathered around me in a circle, and I was told they would give me a piece of advice; what I wasn't told is that they would kick me as hard as I could in the butt so I wouldn't forget their words! It was the most amusing thing I have ever endured, something I will never forget. Of all the 40 some odd kicks in the butt I received, the ones from the other girls hurt the most! As if that wasn't enough, they told me to sit down on the ground, and then proceeded to pour the warm chelas all over my head. It was hilarious, and so very mexican!

By this point, I was supposed to be leaving on Tuesday to go back to the states. On Monday morning, I loaded myself into the Twin Otter and flew back to Puerto with the guys, and my friend Tristan (another traveler who got sucked into the vortex). I promptly changed my ticket to stay an extra week and skydive. Over the course of the week, I did about 10 or so solo jumps, my first 2-way with Tonio, and had the time of my life. I wound up going back to Cuautla for the weekend, at which point Tonio asked me if I wanted to come back to Puerto to work for the week, doing the flight manifest in exchange for jumps. Completely unable to say no (it was becoming a bit like Groundhog Day), I loaded myself once again into the Otter and went back to Puerto, changing my plane ticket yet again. I stayed and worked the week, and it was awesome. I got to jump whenever I wanted, and on Friday I jumped with Pana and Rifle (photos above). It was amazing to fly with friends, and then see it on film later.

I wasn't able to afford staying another week; this time I had to drag myself away from Skydive Cuautla and my newfound family. But it wouldn't be forever. Tonio kept asking me to stay and work manifest in Puerto on the weekdays. I was tempted, but knew it would be a tough one to pull off. I had a life in the states, responsibilities. A yoga class to teach, painting jobs to be done. I was going to turn 30 soon, and felt a pressure to pursue the 'American Dream' and get a career or something going. Despite the voice coming from the angel (or maybe it was a parrot ?) on my shoulder, I barely said my goodbyes, because I would be back, sooner rather than later.

Photos, Top to bottom: Rifle and me, Puerto airport (Photo Daniel "Pana" Angulo); Tonio and Rifle, sit-flying (Photo Pana); Hilary's Mexican skydiving graduation; Rifle and me in freefall (Photo Pana).

A Perfectly Good Airplane

Thinking about what I was doing last year at this time, I realized that today is the one year anniversary of my first tandem skydive. Had this been a one time deal, I might not remember it so clearly, so vividly, nor would the nostalgia be so powerful and consuming. The story goes like this (get comfortable, it isn't a short one, and I am verbose!):

I went to Mexico last year for a 3 week vacation in February. Wanting to learn to surf, I made my way from Mexico City to Puerto Escondido via the Pacific Coast. I immediately fell in love with Puerto Escondido, a surf town with a gigantic beach and a great vibe. Staying in one of the beach hostels, I met a couple of Canadians, Simon and Lylas, and enjoyed spending some time with the two of them, learning to surf and slurping coco locos on the beach. The third day I was there, the skydivers showed up, literally falling from the sky, landing on the hot sand, then setting up their tent in front of the biggest hotel on the beach, The Arcoiris. From here, they recruited travelers to join them for a tandem dive from 15000', over the beach and ocean. Simon was a diver himself, with some 30 jumps under his belt, so he was more than keen to go on his own, and was also intent on recruiting everyone in our hostel to do a tandem. My immediate response was "No way in hell am I jumping from a perfectly good airplane!", and I stuck to my guns. Eventually, most of the hostel had gone and raved about it. After 2 days of watching the divers land on the beach, at sunset, there were only 3 holdouts, Lylas, and British girl called Bella, and me. I was still pretty adament about my position, and the cost of going, but Simon kept at it...and finally, I cracked. My logic was that I was in Mexico, at the beach, and if there ever were a time to do it, it was now. I also thought about my brother, a smokejumper for the US Forest Service, and how he jumps out of the same type of plane, a twin otter. Maybe I would gain some insight into his motivation for doing such a crazy job.

The ride to the airport was completely insane! There were about 15 of us piled into the back of the truck, which raced through town at breakneck speeds, weaving in and out of cars and buses. In hindsight, that was way scarier than jumping out of the door of a plane! Once at the airport, I teamed up with Fernando, a loco Argentinian with wild hair, spanish I could barely understand, and an incredibly warm heart. I suited up in my harness, and we did a 'dirt dive' for practice, with me attached to his harness. He explained the procedure of leaving the plane, and told me what to do with my legs and arms, as well as what to expect once in freefall, and when landing. Honestly, I was terrified! I was sure that I was going to feel like I was falling, my stomache up in my throat, like falling off of something in a dream--that feeling.

Once in the plane, we all cheered at the take-off and enjoyed the view of Puerto Escondido from the air. Feeling nervous, I told myself 'hey, chill out. This dude doesn't want to die, it's going to be fine'. Of course, I was still a wreck, but it was consoling nonetheless.

Unfortunately, we were the last ones out the door, which meant I had to watch everyone else jump out of the plane ahead of me. When we took our position in the door, wind so loud I could barely hear him say 'ready, set, go', I instantly closed my eyes and hoped for the best. As we left the plane, expecting to fall, I opened my eyes in astonishment, realizing that it wasn't falling at all--it was flying! The resistance from the wind of the plane, and reaching terminal velocity, created a feeling of drag, like the air was thick, and movements of your body could cut through it, causing you to turn, and move about like I never imagined possible. My stomach was not in my throat, and there had to have been a ridiculous grin on my face, even though looking at the ground from 15000' feet in the air, over the ocean. Fernando had us spinning in circles so fast I was almost dizzy! The thought of playing around like that moving at about 100 mph or so seemed impossible to me, but we were doing it, and it was awesome!

Once Fernando pulled the chute, around 6000' or one minute of freefall, it was quiet again, and I am pretty sure I let out a big 'woo-hoo'. It was so peaceful to just loaf around up there in this huge lofty parachute, which was controlled by pulling right or left toggle to go right or left respectively. It took about 5 minutes to descend to the landing area on the beach. I wasn't scared anymore, and was pretty devastated that it was over already. Once Fernando put us effortlessly on the ground, I was all smiles, and we posed for the photo above. Tonio, the owner and passionate diver, came over, looked me in the eye and knew I was, for lack of a better word, screwed. He said to me in perfect english: "You are going again, aren't you?"; I'm pretty sure he could see it in my eyes, a glint that not everyone has after jumping from a perfectly good airplane.

February 8, 2006

Friendly Reminder

Luck was on our side, and we woke up to a clear and sunny day in Banos. After breakfast, we hiked up the south side of the Rio Pastaza canyon, hoping for a glimpse of Tungarahua, the active volcano that looms over Banos. At just over 5000 meters (That's 18,500 or so feet), her presence is not to be taken lightly.

After walking a few hundred feet up the road, we saw the summit, covered in snow. I estatically took a few photos, and as I was putting my camera away, a small puff of ash appeared above the cone, then grew into a bigger cloud of ash right before our eyes (see photos above). It was exciting to see, yet left me feeling quite small and vulnerable as I stood and watched the volcano do her thing. Was this normal?, I asked some locals who trundled by. They hadn't even noticed the ash cloud, and answered us with a poliite "Si", when "Por supuesto [of course], stupid gringos" was what the really wanted to say.

Once the mini-eruption appeared to be over, we switch backed our way up the steep road, admiring the scenery. Dotted with small farms, the slopes of the Andes are steep and green, growing much of the produce for the region in the ideal temperate climate of the Pastaza Valley. The Market in Banos is simply rockin'; in my mind, it can't be beat!

Having gained some elevation, we were able to see what a beheamoth Tungarahua really is, as she towers over the surrounding peaks. No small feat in the Andes, where all of the mountains seem ridiculously huge. Seeing Banos in her shadow, one couldn't help but think that Tungarahua could blow her top someday and obliterate the town. The complacency of the locals reminded me of the "Cry wolf" stories we all heard as children: should her warnings be shrugged off as they are? Will the day come that her occasional spewing of harmless ash will be more than just a friendly reminder? We can never know, but I'll bet that she does.

February 1, 2006

Topo Duo

A few days ago, Andy took me down the Upper Rio Tena in a Topo Duo. Experiencing class 4 rapids from the front seat of a two person whitewater kayak was nothing short of exhilerating, if not a bit scary at times. To have a successful run, I had to trust him completely to shout commands at me (no time to ask nicely!) as necessary, as well as trust his judgement as he guided the huge craft downstream, weaving through boulders, snaking around tight turns. It was awesome! I think he pulled it off with more finesse than most people would think possible in a boat of its size, on such a technical little river.

Overall, besides being beautiful and peaceful, the experience greatly influenced my solo kayaking abilities, as I got to experience firsthand what class 4 rapids feel like in the seat of a kayak. I think it could have gone either way, either scaring the crap out of me or making me more keen to run rivers just like that one. Thankfully, it did the latter, and I am now more confident and excited when I am in my own boat, and more eager to be a better kayaker.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)